Global Inflation Watch – The Case For Gold As Future Money

Tyler Durden

Sun, 11/29/2020 – 20:30

Authored by Alasdair Macleod via Goldmoney.com,

This article posits that fiat currencies are on the path to hyperinflation and looks at the evidence in the prices of financial assets and commodities. So far, gold has notably underperformed, which indicates that the early signals of hyperinflation are confined to the cryptocurrencies, whose participants broadly understand fiat debasement, to equities reflecting the desire not to maintain cash and deposit balances, and in international trade, where commodity prices of all stripes have risen in price.

Given that the early warnings of hyperinflation of money supply are here, the article then looks at the qualities required of a sound money to replace fiat currencies.

Introduction

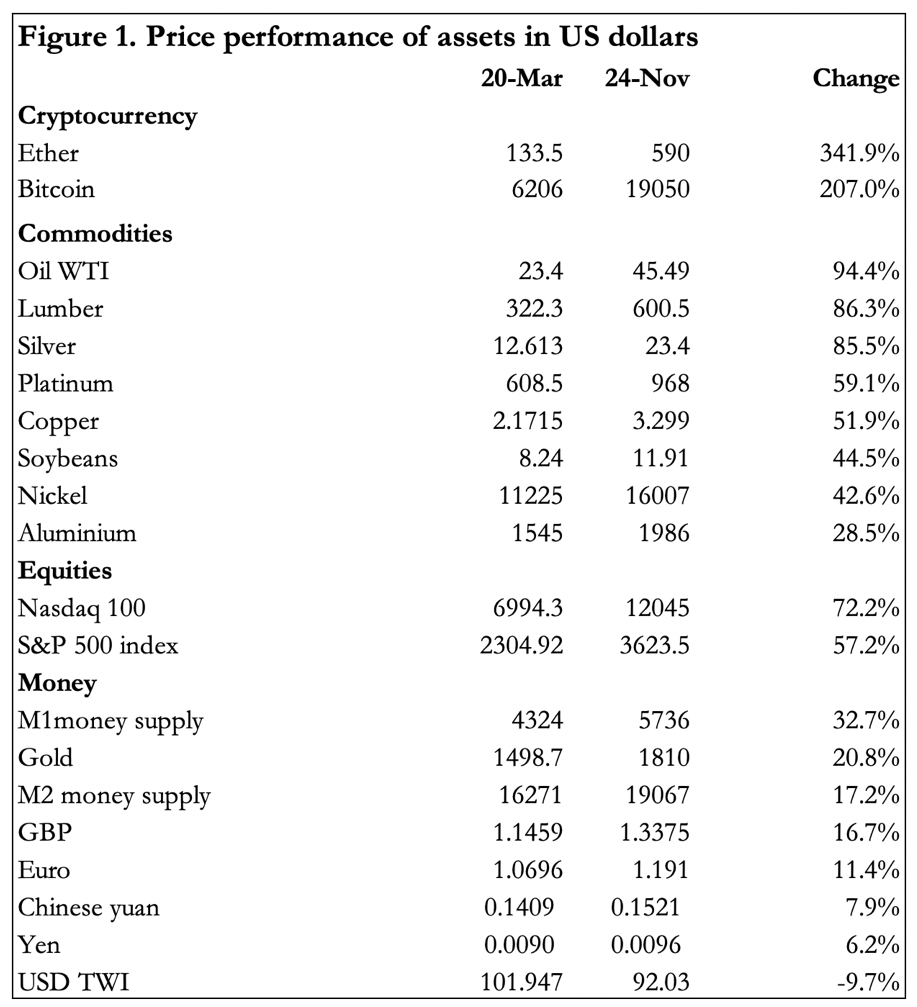

Figure 1 shows how prices have moved from the Friday before the Fed’s announcement on 23 March that it would go all-in on its support for the US economy with unlimited quantitative easing. It amounted to a commitment to hyperinflate the money supply if needed. Before the Fed cut its funds rate to zero on 16 March nearly all these prices were falling.

Since late-March every category has seen increases in prices. Sector and specialist analysts will always claim that there are identifiable reasons why prices for an individual category or commodity have risen. But the fact is that with the exception of the dollar and the other fiat currencies listed in the table all prices have risen. This cannot happen without the dollar and these currencies losing purchasing power.

While being far from exhaustive in its representation, Figure 1 shows that on the back of existing and perhaps anticipated expansion of money supply, cryptocurrencies have seen the most substantial rises. Putting to one side the debate as to whether cryptocurrencies can be a replacement for fiat currencies, in the general population it is their followers who are most aware of fiat currency debasement. In a monetary inflation, the fact that a significant minority of economic actors understand what governments are doing to money early in the hyperinflationary process does not appear to have happened before. It invalidates the old saying that not one person in a million understands what is happening to their money.

More people are flocking to cryptocurrencies, and while they appear to be predominantly driven by the prospect of profit rather than seeking an insurance against the demise of their local currencies, we cannot doubt that most of them have learned the lessons about money that evaded their forebears.

That being the case, we can assume that far from being just a speculative bubble, the rise in prices for bitcoin, ether and other cryptocurrencies anticipates further falls in purchasing power for government currencies, yet to be reflected in the other categories.

The rise in commodity prices varies considerably, but at a time of global economic slump, they are all higher not just in dollars, but measured in the other currencies represented in the table, which can only be a reflection of monetary debasement. Equities have also been strong with the more volatile NASDAQ 100 outpacing the S&P 500 index. And as if to ram the point home commodities and equity prices fell heavily on deflationary fears before the Fed’s unending stimulus was announced in March, only recovering and rising subsequently. The divide between deflationary and inflationary expectations could not be more marked.

Not all items in Figure 1 turned higher precisely on 20—23 March. Gold bottomed at $1452 earlier on 16 March, the day when the Fed cut its funds rate to zero. It rallied before falling to test $1456 on 20 March before closing at $1498.7. Nevertheless, a rise of 20.8% puts it between the increase in M1 money supply and M2. The WTI Oil price went negative on 20 April due to delivery problems on Comex before recovering strongly to rise over 90% on balance from late-March.

In the currencies, only the euro and sterling rose more than the dollar’s trade weighted index fell. And priced in all these currencies, the other items in Figure 1 increased.

The relationship between money and prices

There is usually a time lag between an expansion of the money quantity and its effect on prices, depending on the route it takes to full circulation. The lack of any distinction between existing and new circulating currency conceals its existence. And while every economic actor knows that government money loses purchasing power over time, it is still regarded by transacting parties as having the objective value while variations in price are reflected entirely in the goods or services being exchanged.

If the distribution of new money is channelled through increased government spending targeted at one part of the total economy, then the price effect is initially confined to a few corporations and locations in the sectors concerned, before it spreads to the wider economy before being disseminated by employees, contractors and subsidiary businesses. Alternatively, if money is distributed widely by a representational helicopter, the price effect is more instantaneous because it is more immediately spent mainly on consumer goods.

Even if the additional distribution of new money is made obvious to a population, it fails to grasp the consequences for the dilution of the existing stock of money. Like most analysts in the commodity markets, they initially think that prices are simply rising, and they fail to consider monetary debasement as the cause.

While the simple mathematical relationship between the quantity of money and the effect over time on prices is widely understood, other effects are less so. Changing the amount of money in circulation fatally corrupts statistical comparisons, yet financial analysts appear unaware of the profound differences between today’s money and that of the past. Furthermore, in more normal times the expansion and contraction of bank credit is usually a far larger variation of total money than its expansion by a central bank to fund a government deficit.

But the most profound effect on a money’s purchasing power comes when foreign owners of it domestic users gradually realise that the debasement will continue and even accelerate. Since 23 March, when the Fed told the world it would inflate limitlessly, there were two important categories of actors who immediately understood the inflation message. The first was the cryptocurrency community, as discussed above, and the second was the Chinese government, which accelerated its purchase of commodities, including iron ore, copper and oil. Wheat, cooking oil, and soybeans have followed. Predictably, commentators have seen the ramping up of commodity stockpiles, but not the unseen winding down of dollars. That is the point the Chinese appear to have understood, confirmed by the timing of accelerated commodity purchases. And their currency has also risen by nearly 8% against a weakening dollar, a marked change in official exchange policy.

Hyperinflation of the dollar is here

It is now impossible to envisage the US Government and the Fed limiting further monetary expansions. Their Keynesian creed tells them that to do so would be disastrous for the economy. By relying on macroeconomic beliefs upon which they base their policy decisions they cannot come up with an answer that ultimately saves the currency and the economy. They do not appear to realise that by transferring wealth to a generally non-productive government sector, monetary inflation impoverishes the productive capacity of the economy.

It is against this background that having seen one enormous budget-busting stimulus package from the US Government, we shall shortly see another. Apart from the unconventional cryptocurrency sector and perhaps equity markets, there is little evidence that markets are discounting the inflationary effects of a second package yet — they are awaiting the shape of the next inflationary stimulus. The gold price, having risen by about a fifth since 20 March, is certainly not yet reflecting hyperinflation.

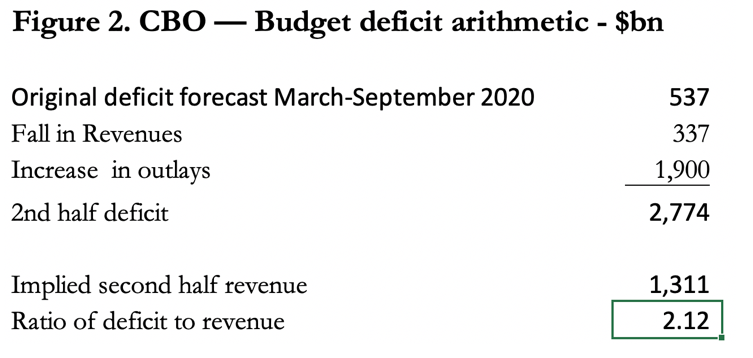

But it is worth looking at US Government finances since March, when the covid response commenced, leading to a fall in tax revenue and an increase in government spending. This is shown in Figure 2.

The numbers in the table reflect the US Government’s financing of federal expenditure following the Fed’s decision to implement limitless QE, and so covers the period of the first wave of coronavirus. From it, we can see that government spending rocketed to 2.12 times tax revenue. This is not so obvious in the annualised CBO figures, where the additional expenditure is spread over the whole fiscal year to September 2020. But with a second half deficit over twice government spending, government financing is roughly one-third by tax revenue and two-thirds by money printing. And this is not going to be a one-off event.

Along with the rest of the world, America has entered a second wave of infections, which will oblige the government to deploy a second similar, or even greater stimulus. The second covid wave is likely to lead to a further fall in tax revenues, as a result of bankruptcies from the initial coronavirus wave combining with the effects of the second. There is also a growing realisation that the economic problems from the virus alone will continue beyond the second wave. This fear is beginning to be reflected in the US Treasury bond market, with yields threatening to rise significantly, as illustrated in Figure 3.

The evidence from technical analysis strongly suggests the low point for the 10-year US Treasury bond yield has now passed and yields are set to rise significantly. That being the case, the Fed will find itself isolated as the only significant buyer as investors increasingly abandon Treasuries as a safe haven investment. And that is before we consider the position of foreign holders of US Treasuries and agency debt, with some of these key players having begun to reduce their holdings.

A further consideration concerning the purchasing power of the next tranche of monetary expansion will come into play. While it is yet to be reflected in consumer prices, with the dollar already diluted by over 30% of additional M1 money between March and September, for the government to obtain the same effect from debasing the currency the expansion of M1 money supply will have to increase by roughly 40% on the expanded base. An aphorism that states for every debasement, a larger one for the same effect will follow, applies. It is the other side of the transfer of wealth from the productive economy to the government which is consistently ignored by macroeconomists. And the more wealth is transferred from the productive private sector to a generally unproductive government, the less there is to transfer. And far from serving to stimulate the economy, these monetary transfers are impoverishing the economy and reducing the government’s tax base at an accelerating pace. The ratio of tax income to inflationary financing illustrated in Figure 2 then rapidly deteriorates from three of inflation to one of tax revenue.

The US Government’s dependency on inflationary financing is already a commitment with no palatable escape. Politicians are trapped by their earlier electoral promises. Assuming Biden is confirmed as the next US President, his left-leaning socialistic policies can only accelerate the debasement process.

As has been the case in many other advanced economies, the US financial system has predominantly supported zombie companies since the Lehman crisis. The increase in unproductive debt has been widely noted. A final collapse of the hampered economy simply cannot be avoided, only deferred. But assuming attempts will continue to be made to defer this outcome, the Fed and the Treasury between them will have to underwrite commercial bank loans and the bank credit extended to businesses that would otherwise collapse. Instead of an understanding of the consequences for hyperinflation of the money supply from covid-19 lockdowns, it will be the realisation that currency debasement must continue to prevent widespread bankruptcies of unproductive, labour intensive businesses that finally awakens the general public to the likely collapse of its government’s money.

The fallacy of the deflation argument

Keynesian economists who see global economic activity badly undermined by covid lockdowns will be confused by the tendency for prices of commodities to rise, because demand for them must be falling. They are almost certain to argue that price rises are probably a short-term aberration, and that lack of consumer demand and oversupply of products will begin to deflate prices. This is reflected in statements from leading central bankers. They envisage that without the support of increasing money supply, the failure of businesses in a deflationary environment will lead to the thirties-type deflation, which fed into multiple bank failures and record levels of unemployment. In other words, they believe there is a growing danger of a self-feeding deflationary slump.

The underlying mistake in the deflation argument was made long ago by dismissing Say’s law. Say’s law points out that we produce through the division of our labour in order to consume. Therefore, in approximate terms an increase in unemployment is matched by loss of production, so the supply and demand of consumer goods broadly remain in balance, but at a lower level of economic activity. The Keynesians only account for falling consumer demand without realising production also declines.

Instead of linking production and consumption through Say’s law, Keynesians imagine a decline in consumer demand due to rising unemployment releases unused production capacity. Understanding this error explains another phenomenon: in a contracting economy people will not increase their cash and deposit balances at a rate to match the expansion of the money supply. Being poorer from the wealth transfer to government through monetary inflation, people tend to reduce their money balances. This alters their money to goods preferences to the detriment of the money’s purchasing power, while more money from the central banks floods the markets.

The reason asset prices rise, followed by those of consumer goods, is a reflection of this desire not to increase money balances, and inevitably, then a tendency to begin reducing them takes hold. Today, this explains the rise in cryptocurrency and equity prices relative to fiat money, driven by the cohorts that are first to ditch a currency which is depreciating relative to their perceptions of financial security.

The Keynesians’ reference point was the appalling depression of the 1930s, which they blamed on gold. With gold, prices fell bankrupting farmers, other businesses and the banks. But farmers with their new tractors increased grain output around the world, the glut driving prices lower for nearly all foodstuffs. At the same time the banks ended a period of credit expansion, withdrawing loans from businesses, creating the usual cyclical slump. The difference from previous slumps was intervention, first by President Herbert Hoover and then by Franklin Roosevelt. It was the prototype Keynesian intervention that prolonged the slump, not the gold standard.

The misunderstanding of inflation-supporting economists and subsequent distortions of the historical truth about the depression have led the economic establishment to fully embrace inflationism, while condemning the deflation of prices as an evil. Again, this flies in the face of historical fact, because prices fell throughout the nineteenth century, improving the living standards of everyone and allowing the purchasing power of their savings to grow. Hard work and innovation were rewarded, while by permitting free markets the government let it all happen under a working gold standard.

One can only suppose that the unadmitted purpose of inflationism is not to improve the prospects for the ordinary individual but to enhance government revenue. That is certainly the outcome of macroeconomic beliefs which condemn deflation.

The case for gold as future money

Some of the reasons commonly put forward denying an inflation problem are notably fiat-centric. For example, a claim that the rise in cryptocurrencies and equity markets are speculative bubbles and not indicative of monetary instability. There is almost certainly truth in this, with a large element of investment always dedicated to trend-chasing rather than founded on reason. But those that take the view it is only speculation fail to get the signal, that what they might describe as unwarranted speculation is an early warning of the consequences of monetary inflation. These are the financial commentators who fail to realise that of any form of money, only sound money can truly reflect a sustainable objective value.

This brings us to metallic money, the gold and silver to which people have always defaulted when kings, emperors and governments fail to sustain their unbacked alternatives. In Figure 1 silver has been included in the commodity category, because with the gold/silver ratio at roughly 77 times it is not being priced for its monetary qualities. That may change. Until it does, we should consider the position of gold as the ultimate money while silver remains priced as an industrial metal, a situation that must nevertheless be kept under review. Furthermore, if governments are to stop the collapse of their currencies, that can only be done by mobilising central bank gold reserves to back them, or alternatively by linking their currencies to another which is fully convertible into gold at every holders’ option.

Apart from other significant hurdles, those who believe that cryptocurrencies will replace gold when fiat dies have the problem of explaining how bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies will be sanctioned as money by governments which have none in their monetary reserves. Instead, they are currently designing their own central bank digital currencies, through which, they hope, they can control economic activity and ultimately prices. If anything, in the face of technological innovation they are spurred on by a determination to keep control of all forms of currency for themselves.

The best hope for cryptocurrencies appears to be that fiat continues to exist and like the Argentine peso, never quite die. If and when they do elapse, or at least when the planners realise their battle is lost and that to prevent a complete monetary breakdown they must introduce proper backing for their currency, then states have the power and the means to ensure sound money is available within a matter of weeks. The only sound medium of exchange they can use is what they have to hand, and that is their gold reserves. Of course, if governments fail to back their currencies convincingly or rein in their spending — necessary to sustain gold backing credibly — cryptocurrencies might have a brief extension as stores of value.

Putting the cryptocurrency issue aside, the history of collapses in the purchasing power of fiat money allows us to rank stores of wealth. The best has always been gold, or other reputable currencies backed by gold and fully accepted by the public as gold substitutes. This time, there are none, so it must be physical gold. As noted above, the debauchment of fiat money impoverishes the private sector until there is no wealth left to be transferred by this means. In consequence, the purchasing power of gold rises to reflect its relative scarcity compared with the capital and consumer goods in the hands of distressed sellers who at the same time reject the government’s currency. Only then can we rank the capital goods relative to each other. Residential property and country estates which produce food come high on the list, as do equities of companies that manage to survive the currency collapse.

But these assets only rise measured in rapidly depreciating government currency. When the paper mark in Germany began its final collapse in 1923 a large house in a fashionable part of Berlin could be had for $100, at $20.67 to the ounce of gold, the equivalent of just under five ounces. Similarly, country estates could be had for ridiculously small amounts of gold-backed foreign currency.

The requirements for monetary flexibility

The argument promoted by bitcoin hodlers is that its future issuance is firmly capped at 21 million, and that with about 18.5 million already issued, of these many have been irretrievably lost. It is simply a supply argument, and if bitcoin replaces failing fiat the price will be sky-high.

This reasoning ignores the fact that a rigid quantity of money in circulation is an unworkable proposition. Prices of consumer items will lack the stability that sound money contributes to transactions. It would become impossible to do the business calculations required for capital investment, because assumptions about future values for both the repayment of debt and the eventual value of the business investment cannot be reasonably assessed. And we must remember that we are moving from a fiat world where through inflation value is transferred from saver to borrower. A significant value-transfer to the saver from the borrower, which would be the inevitable outcome of using bitcoin as the money, would therefore severely restrict entrepreneurial activity and hamper economic progress.

Gold is far more flexible, which is why it has always returned to be the peoples’ money when government money fails. In general terms, mine supply has always increase the level of above ground stocks at a rate similar to the world’s population growth, leading to long-term stability in the general level of prices. Furthermore, a large quantity of gold is not mobilised as money, but for other purposes, mainly jewellery. If the free market demand for monetary gold increases, scrap supply is there to augment gold used for monetary purposes, and if monetary demand diminishes relative to other uses, then scrap supply simply declines.

With gold, there is minimal transfer of value over time from savers to borrowers or vice-versa. The increase in purchasing power that gold-backed savings have enjoyed in the past has come not because of supply constraints of gold, but through competition and innovation of production methods and technology. This certainty always led to savings being protected and available for personal emergencies, retirement, and to pass on to families. And as well as funding personal and family welfare, therefore rendering state welfare provision virtually unnecessary, personal savings provided the monetary capital for businesses and entrepreneurs, who could reasonably calculate the profits from their investment, the money being sound.

Society under a gold standard enables its users to accumulate wealth, because its government, being generally unproductive by virtue of its bureaucracy and monopoly, would have to radically alter its expenditure commitments in order to discard inflationism. In the absence of this source of funding, the cost of government becomes fully exposed, and the tax burden cannot be increased sufficiently to replace it. With sound money, the state has no option but to cut its spending, and to reduce its interventionist roles.

Properly understood by the state authorities, the route to maximising their own power is to let free markets flourish with sound money. This was the wisdom of Britain’s leaders in the nineteenth century, which made this small nation the most powerful on earth. It was also understood by America’s Founding Fathers and America similarly became the most powerful nation after Britain’s decline.

But after decades of fiat money inflation, it is difficult for those steeped in macroeconomics to envisage a world where gold and fully backed gold substitutes are the only money. Much of the paraphernalia of risk management, derivatives and forward markets will no longer be needed and will disappear. Debt can only be taken out on the basis it is repaid when due, and assumptions that it can always be rolled over, or perhaps that the state will come to the rescue must be banished.

Other than the residual role of issuing gold substitutes, of maintaining gold reserves and overseeing the production and free circulation of gold coins, there will be no role for central banks and their planners. Stemming from the UK’s Bank Charter Act of 1844, the laws and regulations that permit the creation of unbacked bank credit should be revised either to make it a criminal offence in line with natural law, or to permit free banking with the removal of limited liability for the managers and shareholders. Only then can the expansion of unbacked money, the origin of which is credit expansion, be reined in. Crony capitalism, whereby an entity gains government support for its operations or to the disadvantage of its competitors, must also cease.

It must be admitted that politicians are unlike to benefit from a sudden Damascene conversion. The only thing that will be clear to them is the need to stabilise the currency, which they will probably have to fight against their own establishments to achieve. There will remain the considerable risk of political anarchy if wise leaders fail to take the public and their administrations with them, raising the prospect of Hayek’s Road to Serfdom.

All that is for the future — perhaps not so distant as we might think — for which cryptocurrencies and central bank digital currencies are not equipped. But today, while there is incontrovertible evidence that some economic actors are beginning to understand that hyperinflation of the money supply is taking hold, the modest performance of the gold price tells us that for the broader public this realisation is still in its early stages.