“We Feel Like We Are Drowning” – Rural Hospitals Overwhelmed By Shortages Of Bed, Staff

Tyler Durden

Tue, 11/24/2020 – 19:05

As the coronavirus ravages rural parts of the US, areas it largely ignored during the spring and summer, hospitals are being overwhelmed.

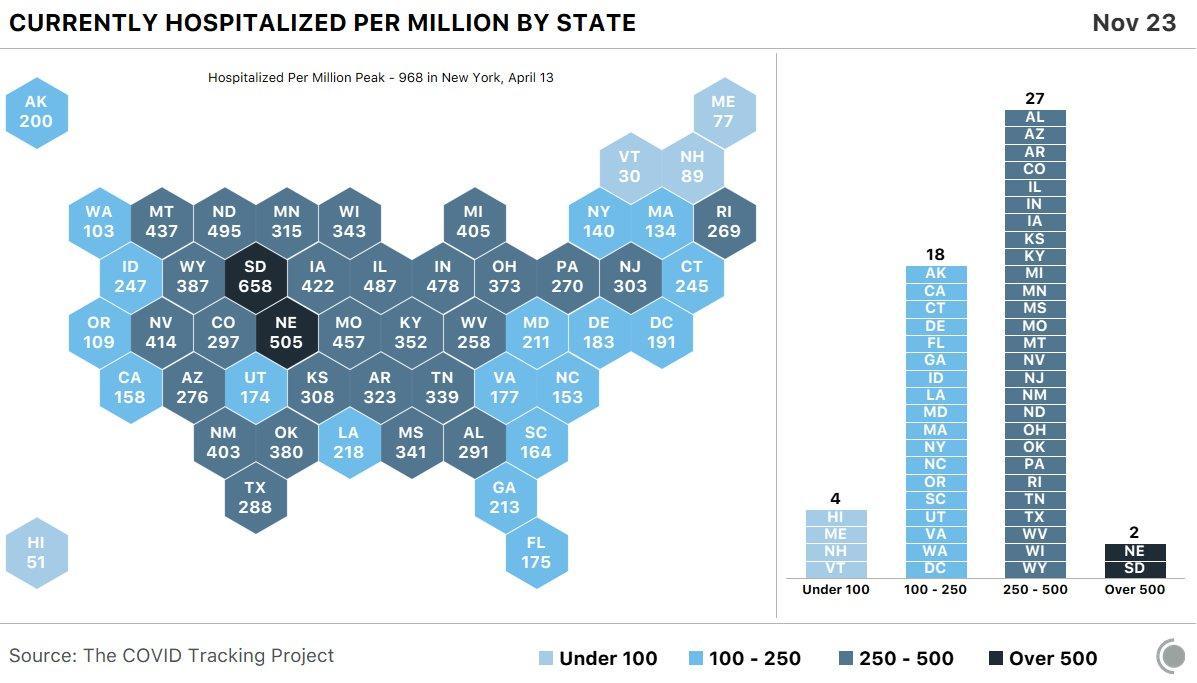

We pointed out earlier that only four US states have hospitalization rates below 100 per million, with the Midwest being the worst hit region, though down in Texas, El Paso has stood out for the severity of its outbreak, and the degree to which deaths have overwhelmed the city’s morgues, forcing Gov. Greg Abbott to send in the national guard.

On Tuesday, Reuters published a story recounting stories from some of the most overburdened hospitals in the country right now. They can be found in places like rural Lakin, Kansas, or other “critical access” hospitals spread out across a dozen states in the midwest and the mountain west. Sparsely populated states like North and South Dakota are being hit particularly hard.

Since mid-June, daily new COVID-19 cases reported in the midwest have increased by 20x. For the week ending Nov. 19, North Dakota reported an average of 1,769 daily new cases per 1 million residents, while South Dakota recorded nearly 1,500 per million residents, Wisconsin and Nebraska around 1,200, and Kansas nearly 1,000. Even during New York’s worst week from April, the state never averaged more than 500 new cases per million people. California hasn’t topped 253.

Across the Midwest, hospital directors told Reuters that they’re at capacity, or dangerously close. Most have tried to increase availability by repurposing wings or cramming multiple patients in a single room, and by asking staffers to work longer hours and more frequent shifts.

Kearny County Hospital in rural Lakin, Kansas is one such example. The hospital is classified as a “critical access hospital” by federal authorities since it’s the only hospital servicing a patch of southwestern Kansas, not far from the border with economically desolate Oklahoma.

Some medical workers complained to Reuters that they see a “disconnect” between the grim scene inside the ICU, and families who are out planning Thanksgiving dinner parties, while some young people continue frequenting bars.

“There’s a disconnect in the community, where we’re seeing people at bars and restaurants, or planning Thanksgiving dinners,” said Dr. Kelly Cawcutt, an infectious disease doctor at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. As health workers, she said, “we feel kind of dejected.”

Dr. Drew Miller, the chief medical officer at Kearny, told Reuters about how he almost lost a 30-year-old patient who needed to be moved to the ICU, but there were no beds. The man survived after he briefly stopped breathing. Dr. Miller said he was astonished when the patient’s pulse returned.

Still, while some forecasters see even more dire numbers ahead, Dr. Miller warned “I don’t think the worst is here yet.”

But for remote hospitals, an even bigger than space is staff. COVID-19 patients must be monitored more closely than others, requiring more nurses to be on duty per shift. When infection rates rise, rural hospitals typically hire from a pool of traveling nurses. However, thanks to the pandemic, that pool is now empty.

Melisa Hazell, a critical care nurse at Hutchinson Regional Medical Center in Hutchinson, Kansas, told Reuters she recently recovered from COVID-19 herself, but she returned to work as soon as she was certain she wouldn’t spread the virus. After being off for 12 days, she said she wasn’t “mentally and physically ready” to go back to work. However “my teammates needed me,” she said.

Thousands of miles away, Mary Helland, a chief nursing officer with CommonSpirit Health in North Dakota, said she has put in requests for traveling nurses for all 11 “critical access hospitals” she oversees, spread across a region covering North Dakota and Minnesota.

But “bigger hospitals are using them all up,” she said. At 190-bed Hutchinson Regional, Chief Nursing Officer Amanda Hullet said she has started taking floor shifts for the first time in years after moving to a managerial position that requires much more desk work. Another nurse said that the refusal of some governors to mandate mask-wearing in public is frustrating. But even people who wear masks are still frequently infected with the virus.

Doctors say trying to change such behavior can feel like a hopeless task. One infectious disease doctor in Wisconsin told Reuters that “Everyone [is] continuing to go about their lives”…but “we sort of feel like we’re drowning.”