Can Poland & Hungary Crash The European Plan?

Tyler Durden

Tue, 12/01/2020 – 02:00

By Elwin de Groot, Maartje Wijffelaars, and Piotr Matys of Rabobank

Summary

- In this piece we take a closer look at the potential implications of a continued deadlock on the EU Budget and Recovery Fund

- What has happened, what are the key issues at handand what are the options to resolve this standoff?

- We ponder the potential impact for the European economy and markets should there be severe delays (or even a breakdown) in the implementation of the Recovery Fund

Recovery Fund held hostage by veto against budget

The EU is in limbo over its next multi-annual budget and, by implication, the Recovery Fund. In the week of 16 November, Hungary and Poland voted down the most recent proposals for the EU’s next multiannual budget, running from 2021 until 2027. Not because they oppose these proposals–in fact they would be among the main beneficiaries of the budget and recover fund-, but out of anger over the new rule-of-law mechanism that was adopted in early November and which is set to come into force next year. The new mechanism is supposed to block transfers of EU funds to countries infringing on EU standards in certain areas such as fundamental rights and judicial independence. This mechanism should protect the financial interests of the EU, i.e. to protect EU tax payers against the misuse of EU funds. Yet Hungary and Poland claim the mechanism to be a vague and therefore a political tool for the EU to interfere with domestic matters. Both countries have been at continuous loggerheads with the European Commission over rule-of-law issues over the past few years. Slovenia also supports the claim put forward by Poland and Hungary.

In any case, whereas the mechanism itself could be and has been adopted by a qualified majority in the Council, the 7y budget, i.e. the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) and Own Resources Decision (ORD), require unanimity in the Council. In addition, the ORD needs to be approved by national parliaments.

Below we look at the immediate implications and the potential scenarios further out.

The implications of a deadlock

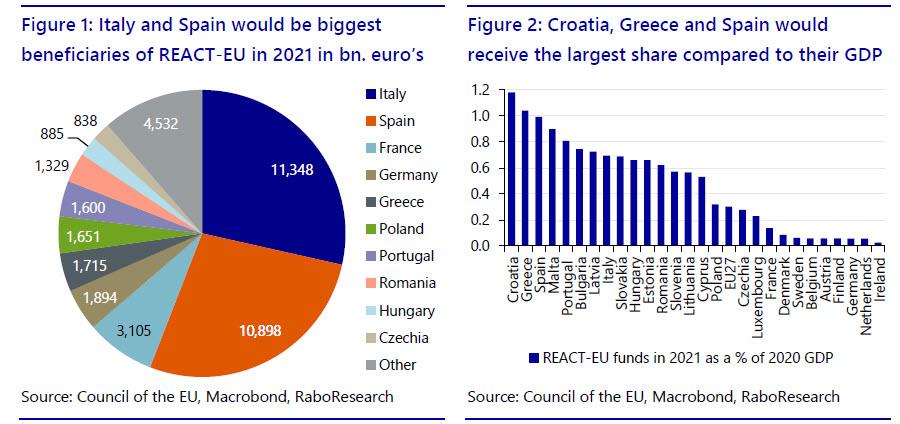

As long as there is no agreement, the current MFF and ORD (2014-2020) would be rolled over. And, as things are looking right now, there will not be such an agreement before year-end. Importantly, this implies that the crisis recovery instrument (Next Generation EU, NGEU) would not see the light of day either. The ORD needs to be revised to provide the European Commission with the mandate to borrow money on financial markets to fund the crisis recovery instrument, among other things. Since the ORD also needs to be approved by national parliaments it is already a given that the NGEU will be delayed and that even if Hungary and Poland will lift their veto in December, crisis recovery funds will likely only start to flow late 2021 at the earliest. To be sure, this was already the assumption for the largest chunk of the recovery instrument, the Recovery and Resilience Fund (RRF, EUR 672.5bn), before the spat, because money from this fund would have to be earned by Member States by achieving reform milestones. Still a small part of the instrument was planned to become available ‘right away’, most importantly REACT-EU funds totaling almost EUR 40bn in 2021 (0.3% of 2020 GDP, figures 1 and 2). Clearly the longer an agreement takes, the more protracted the delay in disbursements of all parts of the new crisis recovery instrument.

Another implication would be that the annual budget for 2021 has to be based on the ceilings in the old MFF and that countries such as the Netherlands will lose their budget rebates. In case an agreement on next year’s budget would also not be reached, the EU will run an emergency budget, allowing it to spend 1/12th of its annual 2020 budget per month in 2021. The 2020 budget not only determines the amounts that can be spent, but also the eligible projects. Funds would only flow to those budget lines that were already present in the 2020 budget. So, for example, already existing cohesion projects in the budget of 2020 that carry over into 2021 can still be financed to some extent, but new cohesion projects cannot.

As for the Rule of Law mechanism, it could be implemented from the start of 2021, irrespective of what happens with the MFF.

What about SURE?

Aside from the RRF, many Member States have been making use of the EC’s SURE fund. The temporary “Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency” is available to Member States that need to mobilize significant financial means to fight the negative economic and social consequences of the coronavirus outbreak on their territory. It can provide financial assistance up to EUR 100bn in the form of loans from the EU to affected Member States on favorable terms to address sudden increases in public expenditure for the preservation of employment. The SURE fund itself would not be at risk from the current standoff. This is in the first place because these are loans apart from the budget rather than grants coming from the budget; and the loans are underpinned by a system of voluntary guarantees from Member States of in total EUR 25bn. Each Member State’s contribution to the overall amount of the guarantee corresponds to its relative share in the total gross national income (GNI) of the European Union, based on the 2020 EU budget. The funding is obtained in capital markets through ‘social bonds’ issued by the EC. Importantly, the EC has already been authorized to raise the EUR 100bn with these bonds via a separate SURE regulation. So, while not fully executed yet, new issuance is not linked to the new ORD and budget. Since its inception, the Council has approved EUR 11.2bn in support for Poland (2.1% of GDP) and EUR 0.5bn for Hungary (0.3% of GDP) – actual disbursements so far are still smaller. In total, EUR 87.9bn out of the total EUR 100bn has already been committed to Member States and final approval on EUR 2.5bn is on its way, bringing total commitments to EUR 90.3bn – EUR 31bn has actually been disbursed.

The current standoff would have no impact on the legal possibility to expand the SURE fund to mitigate the impact of the delayed implementation of the NGEU, if politicians would agree to increase the fund’s size. Given that, as mentioned, the European Commission is authorized to borrow for the SURE fund via a regulation apart from the budget. But to remain creditworthy and be able to borrow at very low rates, either a revision of the ORD, increasing the so-called available headroom, and/ or additional guarantees by Member States would seem to be required. Hence, even if it would be legally possible, it also requires political will, which can be very much questioned both from the side of Poland and Hungary and the other 25 Member States if the current standoff persists.

And the ESM?

Finally, the standoff has no impact on the functioning of the ESM. It could be called to draw a support program if asked for by a Euro area Member State and to activate credit lines within its Pandemic Crisis Support programme linked to the COVID-19 crisis. Remember? The hard fought cheap credit lines Member States can ask for with the only condition for them being that they spend this money on the fight against the health crisis. Indeed, no country has dared to use it, yet, probably out of fear of reputational damage when doing so. Admittedly, given the current, historically low, bond yields in the market, pressure on countries to do so has also been lacking. When push comes to shove (i.e. in case of a long-running standoff and rising bond yields), however, we would still expect EZ Member States to call for them.

Possible scenarios going forward

The big question is whether a compromise can be found on the rule-of-law mechanism or whether talks will remain in deadlock. The next official meeting of EU leaders is scheduled for 10 and 11 December, while finance ministers are due to meet 19 December. It is difficult to predict what will happen and whether either side of the table will blink beforehand. In any case, the risk that no agreement will be found is non-negligible.

One way out, perhaps, is a (non-binding) political declaration (similar to the political declaration setting out the framework for the future relationship between the EU and UK after Brexit) that promises to keep the rule-of-law mechanism at bay, as long as countries do not radically depart from the status quo. This is what the German presidency has proposed.

Yet according to Poland and Hungary such a declaration would be insufficient as it is not legally binding. In fact, on 26 November, Polish PM Morawiecki and Hungarian PM Orban underscored their view saying that the EU should drop the rule-of-law conditionality altogether and that any enforcement mechanism on democratic standards in future would require an amendment in the treaty. The joint declaration signed by both PMs implies that they are not willing to make substantial concessions to overcome the impasse

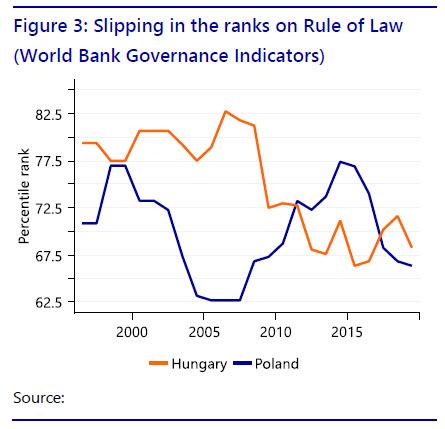

Meanwhile, on the part of European Parliament and most of the other Member States there is a conviction that there should be a strong link between EU funds and the rule-of-law, an opinion that has been building for years. Given that there is a tendency of slippage on this front (see figure 3), putting the mechanism on ice would be a signal to countries to ‘test the boundaries’ of a commitment to delay the enforcement of the mechanism.

Whereas poorer and hard-hit countries might be more willing to soften the tone, others, such as the European Parliament and the Netherlands, have extremely little wiggle room given the sentiment among their rank and file members. Moreover, they know that Hungary and Poland would eventually suffer major economic damage without new EU cohesion fund money and the substantial share of the recovery funds they would be entitled to. As explained below, however, the discussion is not only a matter of economy, but also of sovereignty and ideology. Furthermore, it could take a while before Poland and Hungary would feel economic pain in the event of an emergency budget and no crisis recovery funds.

Why Poland and Hungary may not cave in -for now

One may argue that it is irrational for Fidesz and the Law & Justice party to block the financial package. After all, over the next seven years Hungary and Poland are in line to reportedly receive at least EUR 180bn between them (over 25% of their combined 2019 GDP) from the EU budget and the Recovery Fund. For a short period of time Hungarian and Polish governments may be able to borrow funds from the markets to finance their expenditures, should European transfers be put on hold. However, without cash from the EU, GDP growth will be significantly lower over the long-term horizon and the upward potential for living standards substantially lower.

But, what seems irrational from an economic point of view can be justified by a strong preference to set domestic policies. By blocking the mechanism that would allow Brussels to interfere in domestic policies, PM Orban and PM Morawiecki are fulfilling obligations to their conservative and nationalistic supporters who expect them to fight for sovereignty at all costs, even if the price is as high as EUR 180bn. Conservativism and nationalism are generally perceived as important pillars of support for Fidesz and the Law & Justice. Both parties have also allegedly tightened their grip on the media. This allows them to control the narrative at home and portrait their countries as victims.

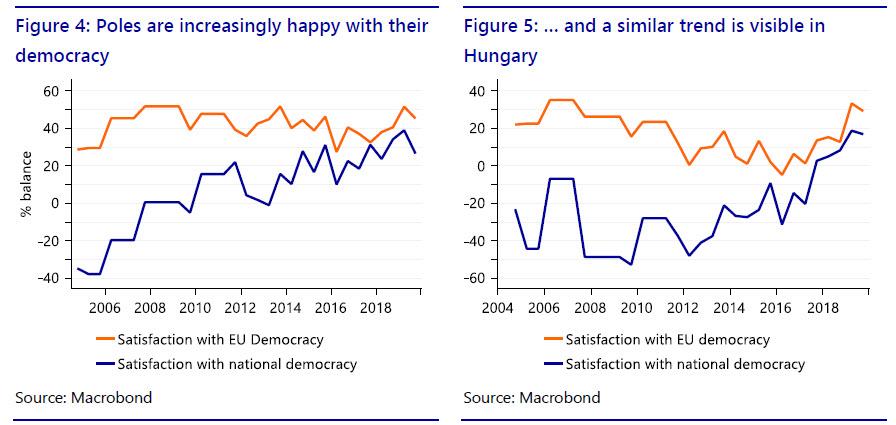

Drawing parallels

Clearly, one can draw some parallels with how Brexit came about and the referendum on EU membership held in 2016 serves as a reminder that ‘nothing is set in stone’. Basically it shows us that the undercurrents in societies can prove very strong. Being able to ‘take matters in one’s own hands’ is one of those undercurrents that has been visible in many places over the last decades. Calls for more sovereignty (and strong leadership) may stem from dissatisfaction with the multilateral framework (which includes the EU) in which countries are operating. This may lead to alienation of voters (as powers increasingly shift from the national to the international level) and rising dissatisfaction with democracy, which is a global phenomenon. Rising inequality could be another source of voter dissatisfaction, which then turns itself on external institutions – if well managed by populist national politicians. To some extent this is what seems to have happened in Poland, for the general public has actually become more satisfied with how democracy is working in Poland (see figure 4) and a similar observation applies to Hungary (figure 5), although the public still is more positive on balance with the EU than with national democracy. However, this also points to another reason for both populist leaders to hold out: they have the support of an increasing number of their people.

Perhaps Hungary’s PM Orban and his Polish counterpart Morawiecki, under pressure from other European leaders, will soften their stance and a compromise can be reached. However, we would not underestimate their determination to fight hard against a mechanism that could potentially force them to ease their grip on power in Hungary and Poland. Reaching a compromise could therefore prove quite difficult in the very near future. This is also because Hungarian and Polish governments may be able to borrow funds from the markets to finance the possible shortfall in European transfers from the budget for a while. Moreover, the rule-of-law mechanism is projected to come into force in 2021, irrespective of whether there will be a deal on the new MFF. Hence, if Poland and Hungary fear they will miss out on EU funds because of this mechanism, they might have less incentive to agree on a new MFF and budget, because it would benefit them less than in previous years.

A different scenario: Bypassing obstructive states

Technically it seems possible to create a separate Recovery and Resilience Fund (the largest chunk of the total EUR750bn new crisis recovery instrument) among willing Member States, outside the MFF. It could be based on an intergovernmental treaty between all EU Member States except for Poland and Hungary – and possibly Slovenia. It might persuade Poland and Hungary to come around on the MFF given their needs for EU funds and weakened bargaining position, but could also reach the opposite, not for economic reasons but by feeding emotions of anger and frustration. We don’t think this scenario is viable in the foreseeable future, for several reasons. First, it would push the EU into uncharted waters and take months at least to talk things through, politically and legally, prior to implementing it. Also because it would likely require paid-in capital from participating Member States. Second, it could make it more difficult to solve the deadlock on the MFF and ORD, which would harm those Member States which depend more on regular budget funds than recovery funds and see budget rebates withheld from certain Member States. Third, it would underscore a failure of EU cooperation, with accompanying risks. That said, as time passes, this option might still become viable in the eyes of most Member States, as the EU would not want to be held hostage by (a few) obstructing Member States.

A track-record of last-minute deals and compromises

Admittedly, the EU has a reputation of sealing last-minute deals. In the past, the EU have shown considerable ingenuity when it comes to interpreting the Treaty, enabling them to do whatever they believe is necessary in the face of opposition from certain Member States:

- Key examples of its ingenuity are the support for Greece in the sovereign debt crisis (despite the prohibition on financial support to Member States), the way it handled the German Constitutional Court ruling on ECB bond buying and, last but not least, the recent COVID-19 response, by (temporarily) watering down state-aid rules and suspending the Stability and Growth Pact;

- The EU has also shown that – when push comes to shove – they can close the ranks, also vis-à-vis those countries that want to move in another direction; the Brexit dossier is a prime example here.

So expect the EU to look for all options/articles in the Treaty that would allow it to come to a solution including all Member States, but also for the cooperating Member States to raise the pressure on Poland and Hungary. For the latter, the key question remains, how sensitive these two Member States will be to financial and political pressures.

What would be the implications for markets?

What is perhaps most remarkable is that the market seems to have largely ignored the potential implications of this situation leading to a protracted stasis. The euro barely budged when Poland and Hungary broke ranks and it has even strengthened against the dollar in recent days. The impact on sovereign spreads has been insignificant as well. This either suggests that markets are not concerned, and/or that market participants have simply been sedated by overflowing liquidity in markets and the ECB’s plans to add even more from December onwards. That said, the Hungarian forint and the Polish zloty were on track to end the last full week of trading in November on the back footing underperforming the Czech koruna.

Still, we would argue, the market may be under-estimating the potential impact from a protracted delay or even a collapse in the EU’s Recovery Fund plans. In that case, the market could yet revise its positive stance on Europe, although we believe the impact will likely be most noticeable in the value of the euro. Some volatility may return in the sovereign bond markets, but the ECB’s PEPP remains the unstoppable force. To add more color to this view we first zoom into how the market has digested the (generally) positive news flow on the European strategy to mitigate the COVID-19 shock.

Looking back (over my shoulder)

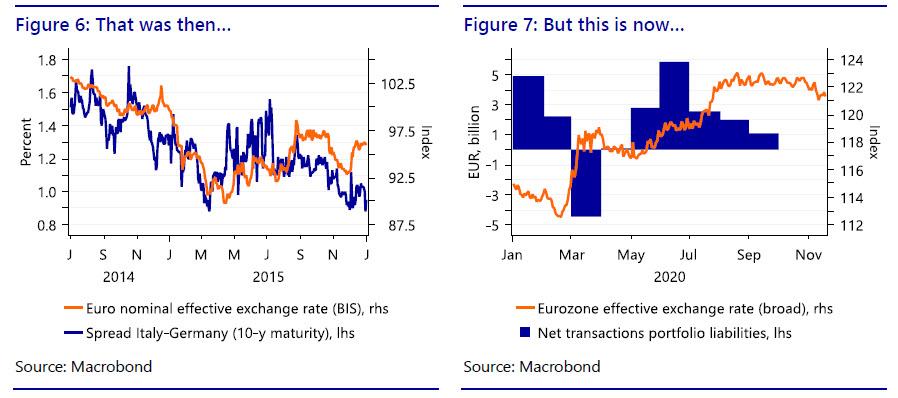

Looking back on the market developments since the ECB launched its Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme, the euro has clearly appreciated while sovereign spreads have declined to new lows. This is an unusual combination of currency and rates moves if we compare it to the ECB’s first venture into quantitative easing: while QE compressed spreads, back in 2015 the additional monetary stimulus also had a profound weakening effect on the currency (see figure 6). Fast forward to 2020, in the wake of the PEPP, spreads have acted the same as before, but it is the –at first glance counterintuitive– response of the euro that caused a breakdown in the correlation between the euro’s performance and peripheral spreads.

Ignoring factors that weighed on the US dollar, the fact that the euro appreciated despite more monetary stimulus can be explained by the one key difference in the pandemic response: the fiscal response. The ECB’s PEPP served as a nod to governments to open the fiscal spigots, which mitigated the economic damage. Moreover, Europe’s surprisingly quick agreement on a joint EU Recovery Fund in July reinforced confidence in the currency union, and in the EU as a whole by pushing back against fears of fragmentation. After an initial selloff of European assets in late Q1, early Q2, foreign investors flocked back into European assets, which was also visible in a rise in portfolio liabilities in the financial account after April (figure 7). Over the summer there was a general perception that Europe successfully contained the coronavirus pandemic, which increased demand for European assets.

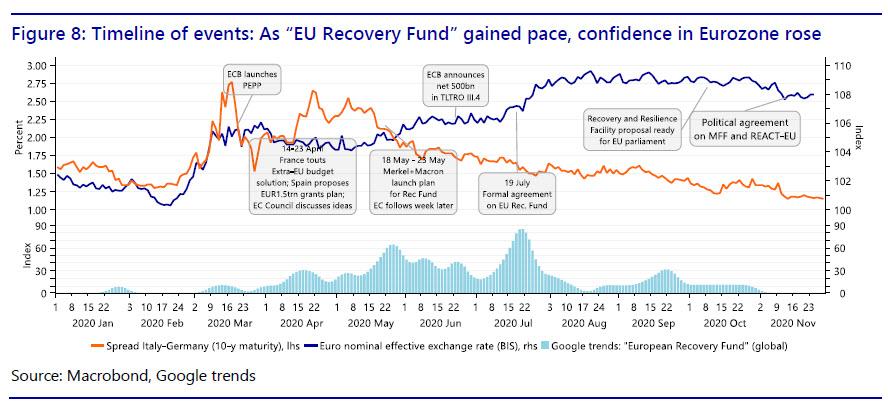

This impact of the Recovery Fund on investors’ confidence in Europe becomes even more obvious if we look at the three phases toward an agreement (figure 8 below). These three phases are also well-illustrated by the news flow and search behavior on Google, which basically shows that the market turning points coincide with the peaks in the search activity for phrases related to the Recovery Fund:

- The first serious discussions on an EU Recovery Fund started in April following the ECB’s pandemic support package announced in March and pressure from the ECB on the EU to take up the baton; in that early phase (April-May) there was still considerable uncertainty, in part because of the hardline stance by (initially) Germany and the ‘frugal four’ Member States. In this stage, when the ECB was still at it alone, it was mainly sovereign spreads that were affected.

- But as the pressure on Europe grew and Chancellor Merkel and French President Macron launched their plan on 18 May (which was followed by the official EC plan one week later), the opinion among investors started to shift. Mid-May is also a clear turning point for the euro, while the proposal stopped the renewed widening of sovereign spreads in its tracks.

- Confidence in Europe was given another boost by the unexpectedly swift (preliminary) agreement in the European Council on the EC plan on 19 July, which, importantly, paved the way for a common EU debt asset as from 2021. Investors interpreted this as a positive signal with regard to the ability and decisiveness of ‘Brussels’ and importantly as a confirmation the euro is here to stay; the euro strengthened well into the summer, reaching multi-year highs in trade-weighted terms in August.

What if… and then what?

Having established that at least part of the recent strength in the euro has been down to the ‘successful’ flight of the Recovery Fund plan and that, in its wake, sovereign risk premiums have only further tightened, this obviously raises the risk that if the Recovery Plan runs into significant delays we could expect part of that positive sentiment to reverse. Even worse, of course, would be a total collapse of the plan, as that would imply (how unpalatable or even unlikely that may sound) that the market will again start to question the whole European project.

So basically we can envisage two scenarios: either one side ultimately blinks, or the spat between Poland & Hungary and the rest of the EU blocks the implementation of the new EU budget. Technically speaking, a third scenario could be a circumvention of the Hungarian/Polish budget blockade altogether, but that would perhaps be more of an extension of the second scenario.

Either side blinks

It is still possible that either Poland and Hungary or the other Member States blink in the upcoming months – whilst signaling during the process that there is no definitive break. That could still pave the way for an agreement on the multi-annual budget. After all, as we argued above, Europe is known for its eleventh-hour deals. While this may still see some delays in the actual implementation of the Recovery Fund –largely owing to the need of national parliaments to ratify the amended ORD– the economic and market impact should be relatively limited.

National governments may need to pre-fund more of their spending plans, but the limited and temporary nature –and the continued presence of the ECB– should keep sovereign spreads from widening significantly. However, if the standoff persists in the coming weeks and the ratification is delayed beyond 10 December, that could lead to temporary pressure on the euro, but –like the standoff– this should not last in this scenario. As outlined in his latest note available here Piotr definitely sees the risk of a short-term squeeze higher in EUR/PLN and EUR/HUF on the back of growing tensions between Hungary/Poland and the rest of the EU.

Budget blockade

If, however, both sides stick to their red lines, this could block the EU budget for a protracted period, since it needs to be ratified by all EU members. This would put the EU on rations, and it would lead to much more severe delays in the time lines for the Recovery Fund. That puts more pressure on countries’ fiscal metrics; and would lead to lower-than-expected revenues from the EU, especially from 2022 onwards.

The severity of lost income differs per country and region, but crucially, those with weaker government finances also stand to lose more – particularly by omission of the Recovery Fund. These governments will have to cut back on their spending, or get themselves into more debt to continue boosting the economy. Either way, without the European funds, the economic recovery is likely to be less inclusive, and therefore less strong. Add to that the doubts it would cast on the newfound European solidarity.

Again, this is likely to weaken the euro as investors lose confidence in the continent and the currency. Meanwhile, reduced growth prospects and/or higher indebtedness are likely to exert upward pressure on spreads. With the ECB’s purchasing programs still in place, spread widening is likely to remain limited, but volatility is likely to increase as spread drivers would no longer be unidirectional. The question is then how much the ECB needs to intervene, and these interventions are then more likely to weigh further on the currency. In effect, this would bring us back to the 2015 period when quantitative easing was first started. Moreover, looking a bit further ahead, the lower growth prospects for Europe in this scenario would give more impetus to the ‘lower for longer’ rates environment.

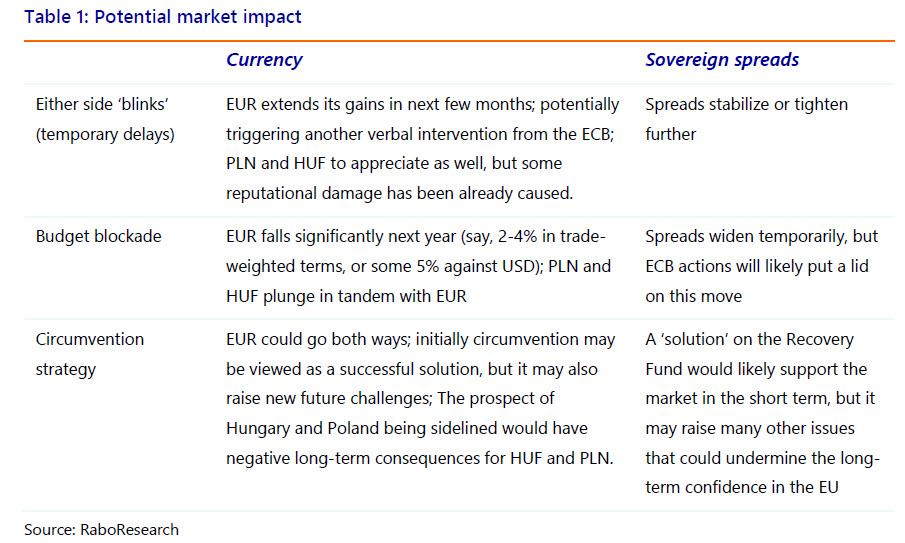

The table below gives some indications for the direction, duration and extent of any of these three scenarios, although we have to stress that this is a good deal of expert judgment.

In short

The outcome of the current standoff is uncertain. While the EU is known for its eleventh-hour deals, the risk that no agreement will be reached in the Council’s meeting in December is non-negligible. This is especially because there is more at play than ‘plain’ economics. Identity and sovereignty are also part of the discussion – and this is by no means the first case at hand.

Should Hungary and Poland uphold their veto for a protracted period, especially poorer regions and countries hard-hit by the crisis will feel the pain. A protracted period of uncertainty could dent the euro in currency markets, although we feel that significant volatility in bond markets is likely to be attenuated by ECB policy actions if required.