Fed, IMF Sound Warning That More QE Could Lead To “Unintended Consequences”

Tyler Durden

Wed, 11/25/2020 – 15:44

Five years ago we wrote that the world’s most exclusive club has eighteen members. They gather every other month on a Sunday evening at 7 p.m. in conference room E in a circular tower block whose tinted windows overlook the central Basel railway station. Their discussion lasts for one hour, perhaps an hour and a half. Some of those present bring a colleague with them, but the aides rarely speak during this most confidential of conclaves. The meeting closes, the aides leave, and those remaining retire for dinner in the dining room on the eighteenth floor, rightly confident that the food and the wine will be superb. The meal, which continues until 11 p.m. or midnight, is where the real work is done. The protocol and hospitality, honed for more than eight decades, are faultless. Anything said at the dining table, it is understood, is not to be repeated elsewhere.

Few, if any, of those enjoying their haute cuisine and grand cru wines— some of the best Switzerland can offer—would be recognized by passers-by, but they include a good number of the most powerful people in the world. These men—they are almost all men—are central bankers. They come to Basel to attend the Economic Consultative Committee (ECC) of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), which is the bank for central banks.

The conclaves have played a crucial role in determining the world’s response to the global financial crisis. “The BIS has been a very important meeting point for central bankers during the crisis, and the rationale for its existence has expanded,” said former BOE governor Mervyn King. “We have had to face challenges that we have never seen before. We had to work out what was going on, what instruments do we use when interest rates are close to zero, how do we communicate policy. We discuss this at home with our staff, but it is very valuable for the governors themselves to get together and talk among themselves.”

Those discussions, say central bankers, must be confidential. “When you are at the top in the number one post, it can be pretty lonely at times. It is helpful to be able to meet other number ones and say, ‘This is my problem, how do you deal with it?’” King continued. “Being able to talk informally and openly about our experiences has been immensely valuable. We are not speaking in a public forum. We can say what we really think and believe, and we can ask questions and benefit from others.”

The conversation is usually stimulating and enjoyable, say central bankers. The contrast between the Federal Open Markets Committee at the US Federal Reserve, and the Sunday evening G-10 governors’ dinners was notable, recalled Laurence Meyer, who served as a member of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve from 1996 until 2002. The chairman of the Federal Reserve did not always represent the bank at the Basel meetings, so Meyer occasionally attended. The BIS discussions were always lively, focused and thought provoking. “At FMOC meetings, while I was at the Fed, almost all the Committee members read statements which had been prepared in advance. They very rarely referred to statements by other Committee members and there was almost never an exchange between two members or an ongoing discussion about the outlook or policy options. At BIS dinners people actually talk to each other and the discussions are always stimulating and interactive focused on the serious issues facing the global economy.”

All the governors present at the two-day gathering are assured of total confidentiality, discretion, and the highest levels of security. The meetings take place on several floors that are usually used only when the governors are in attendance. The governors are provided with a dedicated office and the necessary support and secretarial staff. The Swiss authorities have no juridisdiction over the BIS premises. Founded by an international treaty, and further protected by the 1987 Headquarters Agreement with the Swiss government, the BIS enjoys similar protections to those granted to the headquarters of the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and diplomatic embassies. The Swiss authorities need the permission of the BIS management to enter the bank’s buildings, which are described as “inviolable.”

(For more on the secretive group that runs the world read our background post on the BIS).

* * *

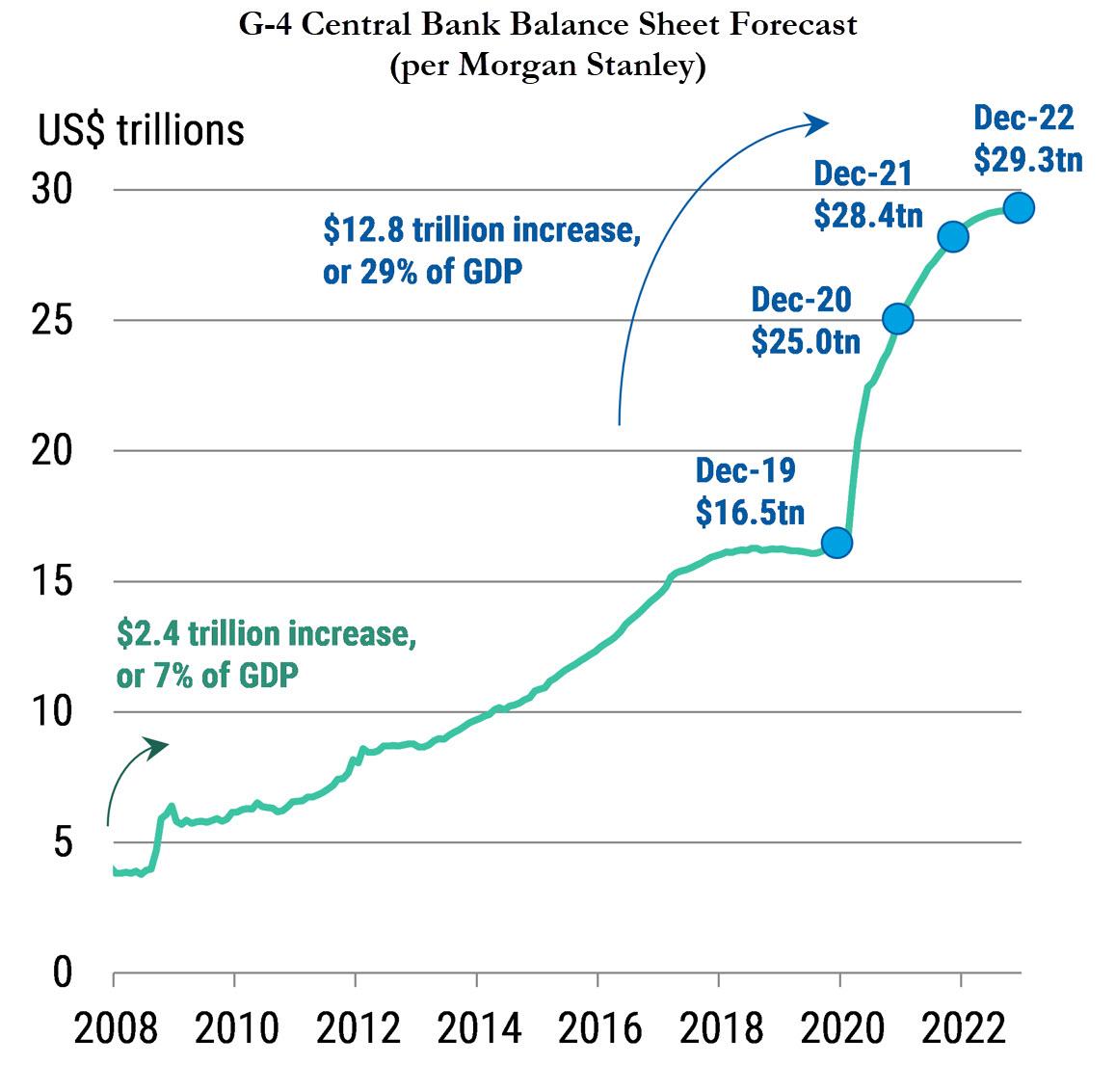

It is perhaps at one of these recent dinner events at the most important dining room table in the world that the world’s central bankers saw a variant of the chart below, which shows that unprecedented expansion of central bank balance sheets:

What the chart shows is that, as BofA CIO Michael Hartnett put it so eloquently two weeks ago, as of this moment, central banks are purchasing an unprecedented $1.2 billion in assets every single hour… and there is no end in sight.

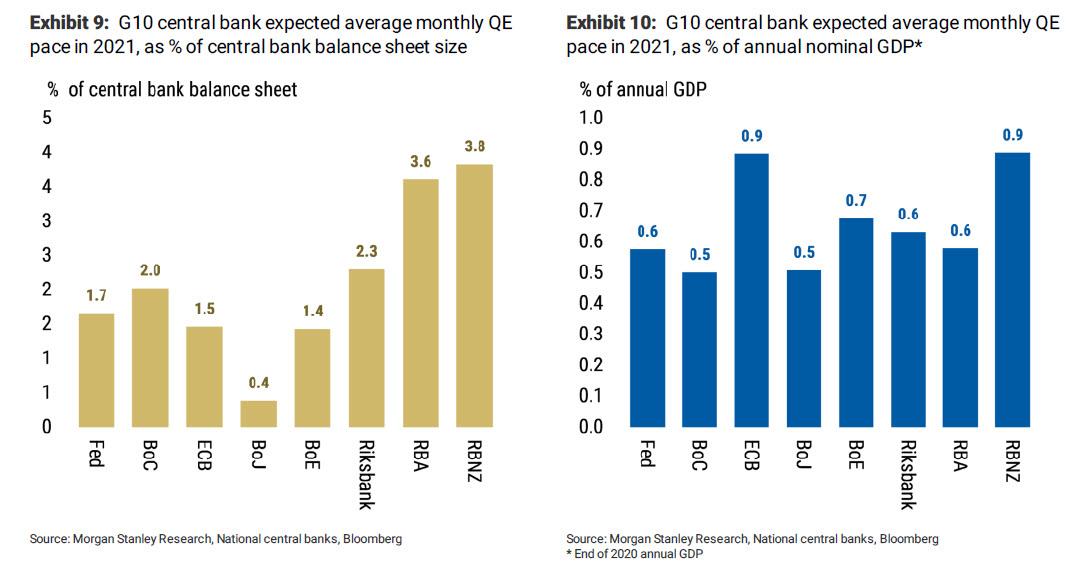

As another strategist, Morgan Stanley’s Matthew Horbach, framed this firehose of liquidity just the 8 DM central banks which will be active in 2021 are expected to add liquidity worth 0.66% of annual nominal GDP, on average, every month in 2021. “That is a rapid pace of global liquidity injection, the likes of which we haven’t seen outside of 2020” Hornbach casually inserts.

Needless to say, this is all very troubling not in the least because it is obviously expanding what is already the biggest asset bubble of all time: troubling, because while both US and global stocks are currently at all time highs, this has only been made possible thanks to the relentless, record firehose of central bank liquidity that is openly propping up asset prices. Indeed, we have gotten to the point where even established strategists cast aside the lies and admit that liquidity is all the matters, as Hornbach did when he said that “central bank liquidity both greases the wheels of transactional finance and changes the opportunity set available to investors.”

Now, central bankers – dumb career academics as some of them may be – are not all idiots, and they clearly understand that what they are doing is merely buying time while in the process making a massive bubble even bigger, so much so that when the next crash comes, it could mean the end of fiat currency and western capitalism as we know it, especially if central banks lose what little credibility they have.

It may also explain why, amid the generally cheerful commentary in today’s FOMC Minutes, according to which FOMC “participants saw the ongoing careful consideration of potential next steps for enhancing the Committee’s guidance for its asset purchases as appropriate”, there were two distinct warnings that the Fed’s $120BN in monthly QE could lead to catastrophic consequences.

Of course, the Fed would never use alarmist language like that. Instead what the minutes did say was subdued, but just as alarming, to wit:

- Several participants noted the possibility that there may be limits to the amount of additional accommodation that could be provided through increases in the Federal Reserve’s asset holdings in light of the low level of longer-term yields, and they expressed concerns that a significant expansion in asset holdings could have unintended consequences.

- A few participants expressed concern that maintaining the current pace of agency MBS purchases could contribute to potential valuation pressures in housing markets.

What this means translated into simple English, is that the Fed itself is starting to have doubts that its shotgun approach of stimulating the markets, or rather “the economy” as they call it, may be reaching its limits and that the next major expansion in QE could have “unintended consequences”, i.e., a market crash. And just as bad, they also concede that just the current $40BN in MBS purchases could lead to another repeat of the housing bubble of 2006/2007… and its inevitable bursting.

Of course, such warnings come and go; meanwhile what the Fed also said is that for all its concerns, it will most likely continue to pump liquidity, as the central bank is absolutely mortified of another crash – as only then will its lack of tools to sustain financial markets become apparent. As such, the Fed will do everything in its power to not only short circuit the business cycle in perpetuity, but also avoid any market drops… ever again. This is what the Minutes also said:

- Participants noted that the Committee could provide more accommodation, if appropriate, by increasing the pace of purchases or by shifting its Treasury purchases to those with a longer maturity without increasing the size of its purchases.

- Alternatively, the Committee could provide more accommodation, if appropriate, by conducting purchases of the same pace and composition over a longer horizon.

- While participants judged that immediate adjustments to the pace and composition of asset purchases were not necessary, they recognized that circumstances could shift to warrant such adjustments. Accordingly, participants saw the ongoing careful consideration of potential next steps for enhancing the Committee’s guidance for its asset purchases as appropriate.

- Few participants indicated that asset purchases could also help guard against undesirable upward pressure on longer-term rates that could arise, for example, from higher-than-expected Treasury debt issuance.

And while we understand the tight constraints under which the FOMC operates – where every word is scrutinized under a microscope – the IMF does not have such limitations. Which may explain some surprisingly honest warnings from its managing director, Kristalina Georgieva, who yesterday said that the pandemic-induced collapse in activity has put central banks under pressure to deliver more rate cuts and policy accommodation, but “more of the same is not possible and will not be sufficient today.

As Georgieva explained (clearly paraphrasing words that were spoonfed to her by someone with far greater experience with the capital markets) with rock-bottom rates and low or negative bond yields, central banks are “going back to the lab, reviewing their frameworks to identify innovative strategies and tools that will support the recovery from this crisis and beyond.”

But the punchline is when she warned that “new strategies and tools might produce new side effects as well,” and “additional monetary stimulus may pose important risks to financial stability.”

That’s right: not only did “several participants” warn about “unintended consequences” in case of a “significant expansion in asset holdings”, but the IMF explicitly now warns that additional stimulus may leads to “important risks to financial stability.”

And just in case the message was missed, the IMF head next said that “monetary policy makers will need to balance a short-term boost to inflation and output against a buildup of macro-financial vulnerabilities.”

Separately, Tobias Adrian, the IMF’s monetary and capital market director, issued an almost similar warning arguing that central banks should consider “not only the path of output, unemployment, and inflation, but also expected macro-financial stability, with the proposed approach capable of jointly quantifying risks to all these variables.”

In summary, the IMF’s recommendation was the old fallback: “Monetary policy should not and cannot do the job alone” and that “fiscal policy has a significant role to play.” Which is great in a world where politics still functions; unfortunately as the hyperpolarized political environment in the US so vividly shows, major fiscal stimulus may remain a mirage until 2022 unless the Democrats win the January Georgia runoffs.

Which then means that it will once again be up to the Fed.

And while stocks and bonds have been delighted by this eventuality, surging to record highs as new trillions in QE means just one thing – even higher asset prices, one wonders if we are now on the verge of a Rubicon where, if “several participants” in the FOMC and the head of the IMF are correct, the next QE fails to lift stocks but instead triggers the next crash.