JPMorgan: Powell Is At Risk Of Losing His Job

With Fed Chair Powell’s term expiring in February, debate is starting to swirl about his fate: will Biden keep him, grateful for monetizing all the trillions in stimmies the president has unleashed to purchase votes kickstart hyperinflation, or will more progressive elements in the Democratic party hold out for an even more librrrral Fed chair.

According to WSJ’s new Fed-whisperer, Nick Timiraos, Powell "who enjoys broad support in markets and among lawmakers from both parties" is viewed by some inside and many outside the administration as the front-runner for the job, but if Biden decides he would prefer his own pick, rather than the Republican chosen by President Trump, Fed governor Lael Brainard is the most likely candidate to succeed him. More:

Some Democrats want Mr. Biden to replace Mr. Powell. They prefer the White House name a woman or member of a minority to lead the central bank as part of a broader push for diversity at the top ranks of the U.S. government. “Leaving aside my policy differences with the current leadership of the Fed, it would be a huge missed opportunity to reappoint a conservative white male as Fed chair,” Graham Steele, a former Democratic Senate aide, wrote in a tweet last year. Mr. Biden announced his intent Monday to nominate Mr. Steele to a top Treasury Department post.

But while the WSJ’s conclusion was ambiguous and did not hint at either outcome as more likely, JPMorgan’s chief economist, Michael Feroli, was more definitive warning that "Fed chair Powell faces an uphill challenge in securing a second term as Fed chair" adding what we already know namely that "if Biden opts for change, Governor Brainard is positioned as the leading contender."

Feroli starts off by praising Powell’s response to the COVID-19 financial crisis and recession which "was aggressive, creative, and determined; his leadership during that period has justly received applause from economists and legislators across the political spectrum." Praise notwithstanding, Powell "is now at risk of losing his job."

As he further notes, even though the framework review that he led moved monetary policy in a direction favored by progressives, the Fed has responsibility for more than just monetary policy (see "The Central Banks New Mandate: Social Justice, Race, Gender Issues, Climate Change And Inequality"). Given the central bank’s significant regulatory and supervisory powers, Feroli thinks that left-leaning voices in the administration likely will not want a Republican like Powell to remain chair, and thus JPMorgan sees "a significant chance that Powell is not nominated to serve another four-year term as chair after his current term expires in January. (Moreover, even though Powell’s term as governor goes to 2028, we suspect he would resign if not re-nominated as chair)."

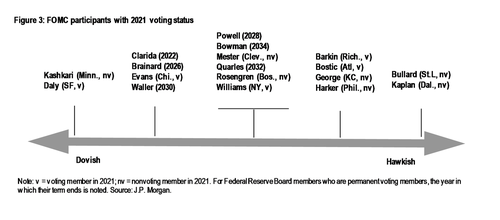

If Powell isn’t nominated, Feroli thinks governor Brainard is the most likely replacement. Brainard has been a governor since 2014 and generally has been viewed as one of the more dovish members of the FOMC. Equally important for her chances of being nominated, "she has favored a more activist use of the Fed’s regulatory powers. Given her stated views on the economy and monetary policy, it is reasonable to conclude that a Chair Brainard would continue to tilt monetary policy in a dovish direction."

Other names that have been mentioned as possible Fed chairs include Michigan State professor Lisa Cook and Howard University professor and AFL-CIO chief economist William Spriggs. While less is known about their views on monetary policy, it’s clear from their public comments and research that they would also place strong emphasis on the Fed’s full employment mandate. Any of these candidates—Brainard, Cook, or Spriggs—would almost certainly reinforce the Fed’s current dovish stance. However, the Fed’s current policy stance is already laser-focused on providing accommodation. This raises the bar for how much more dovish any of these candidates can push the Committee.

In addition to a new chair, next year the Fed could see a few other changes in key positions.

- First, there’s still a vacancy on the presidentially-appointed Board.

- Second, it’s pretty clear that Quarles will not be nominated for another term as vice chair of supervision when his term in that role ends this October. However, he has indicated that he may stay on as governor even if he loses his leadership role (his term as governor ends in 2032).

- Third, Vice Chair Clarida’s term as governor and vice chair ends next January. Even though he spear-headed the framework review that should further the administration’s economic priorities, the same political dynamics that may put Powell’s job at risk could also affect Clarida.

As Feroli concludes, these decisions could interact; if Quarles and Clarida departed the administration could be assured of a Democratically-controlled Board even with Powell as chair.

* * *

That said, no matter how the DC politics play out, JPMorgan believes that the Board is almost certain to remain focused on the Fed’s employment mandate next year, which was recently reinterpreted by the Fed’s framework review. The Fed will now no longer seek to minimize deviations from full employment, but rather shortfalls from full employment. To be sure, even Feroli is unsure how this will materially change how the Fed conducts policy as "it’s hard to find instances where the Fed tightened policy only because unemployment was too low (though it has hiked when low unemployment was forecasted to lead to inflation)."

The review also changed the employment mandate to be “broad-based and inclusive.” Conceptually, there is no simple way for the Fed to use one tool, the interest rate, to target differing objectives. In fact, many have argued that using such a simple, blunt tool, will only lead to even more labor market distortions while blowing the already biggest asset bubble in history even bigger.

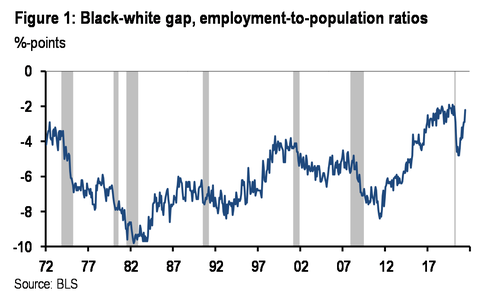

As a practical matter, the FOMC may get "bailed out" by economic developments. One prominent dimension of a more inclusive labor market is the narrowing of black-white employment outcomes (Figure 1). Some of this narrowing has come from a deterioration in white prime-age labor force participation. In any event, the broad-based and inclusive clause may be a check the Fed doesn’t have to cash.

If this understanding is correct, then FAIT should at the least seek to move inflation expectations (here proxied by the Fed’s Index of Common Inflation Expectations) back to where they were before the Fed began its most recent hiking cycle.

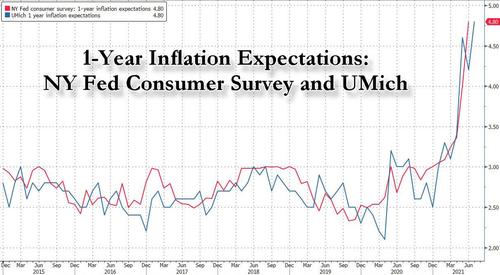

Beyond that, the practical implication of the new framework will be policy that maximizes employment subject to the constraint that inflation expectations do not break out of the historical range, which when it comes to consumers, we already know they have through the 1-year point. Should inflation not revert to baseline fast, the Fed will be in deep trouble.

Finally, Feroli also cautions that there is "a modest risk that if a leadership transition is viewed as too extremely dovish by the market, this may ironically induce a more hawkish policy response to insure the Fed hasn’t completely lost inflation-fighting credibility." He goes on:

When President Reagan surprised the market on June 2, 1987, by nominating the perceived dove Alan Greenspan for Fed chair the dollar weakened and the 10-year Treasury note sold off 27 basis points on the day. From his first day as chair on August 11, 1987, until Black Monday on October 19, 1987, the Fed hawkishly surprised the markets, and the minutes indicate it was motivated by concerns that the markets were losing faith in the Fed’s inflation credibility.

This risk would only become a consideration if market-based inflation expectations—and inflation expectations more generally—moved into a range that was materially and persistently above the Fed’s 2 percent average inflation goal. Given that the market – if not consumers – has taken FAIT in stride, this is probably a pretty low risk, particularly if the next chair is already known to market participants.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 07/22/2021 – 11:34