Taibbi: Will “Goldman Penis Envy” Crash The Economy Again?

Authored by Matt Taibbi via TK News,

Nearly fifteen years ago, on December 10, 2006, the CEO of Senderra, a subprime mortgage lender owned by Goldman, Sachs, sent a grim report to its parent company. “Credit quality has risen to become the major crisis in the non-prime industry,” Senderra CEO Brad Bradley wrote, adding that “we are seeing unprecedented defaults and fraud in the market.”

Within four days, senior executives at Goldman decided to “get closer to home” by unloading risky mortgage instruments. They didn’t alert regulators, of course, but did save their own hides, with Goldman CEO Lloyd Blankfein soon after ordering subordinates to sell off the ugly “cats and dogs” in their mortgage portfolio.

Around the same time that Goldman was having its come-to-Jesus moment, rival Lehman Brothers was going the other way. In one meeting, the bank’s head of fixed income, Mike Gelband, pounded a table, telling the firm’s infamous Vaderqsque CEO Richard “Dick” Fuld and hatchetman-president Joe Gregory there was a $15-18 trillion time bomb of lethal leverage hanging over the markets. Once it blew, it would be the “grandaddy of credit crunches,” and Lehman would be toast.

Fuld and Gregory scoffed. They didn’t understand mortgage deals well and thought Gelband lacked nerve. “Be creative,” they told him, adding, “What are you afraid of?”

“We called it ‘Goldman Penis Envy,’” says Lawrence McDonald, former Lehman trader and author of A Colossal Failure of Common Sense. In telling the Gelband story, he explains that Fuld and Gregory were so desperate to beat out Goldman and become the richest men on Wall Street, they chased every bad deal at the peak of the speculative bubble.

“These tertiary financial institutions, in order to win business away from the big players, they have to continually juice their offerings, offer more leverage, more goodies,” says McDonald. “Dick and Joe, they wanted to do these banking deals, to steal Goldman’s business by offering more.”

In the end, Goldman got out just in time, and Lehman – which had scored record profits in every year from 2005 through 2007, pulling in $19.3 billion in revenue in 2007 alone – became a bug on the windshield of history.

In the triggering episode, Goldman was the first bank to smell a rat in AIG’s financial products division and demand collateral calls to AIG swaps, just before AIG imploded. Goldman ultimately got bailed out in its AIG dealings by the Fed and the taxpayer to the tune of a hundred cents on the dollar, while the collapse of Lehman’s portfolio of bonehead deals sent them into bankruptcy and helped trigger a global chain reaction of losses that cost Americans $10 trillion in 2008 alone.

It feels like déjà vu all over again. We’re in a frothy economy where banks are pouring money into the worst conceivable deals, upselling the most dubious clients in an effort to outdo each other, resulting in huge losses. Just like in 2008, the warning signs are being ignored.

The narrative started in January, when GameStop captured the public imagination. The struggling retail video game company, targeted by short-sellers, saw its share price shoot from $6 to $347 in a few months, spurring elation among Redditors and day-traders who’d bet the stock.

Wall Street pundits threw a fit over GameStop because for whatever else was going on there, there were outsiders trying to break into a rigged game, which was deemed unacceptable. Across the political spectrum, there were howls of outrage and calls for official probes of all involved, down to YouTuber-in-ski-hat Keith Gill, a.k.a. “Roaring Kitty,” who had the temerity to invest $745,991.

While GME gobbled headlines, other short-targeted companies saw wild jumps. GSX, a Chinese online tutorial firm shorts had circled since last year, moved from $46 on January 12th to $142 fifteen days later. Baidu, a Chinese Internet services firm some claimed used shady reporting practices, went from $133 in late November to $339 in February. Viacom, the most heavily shorted media stock, went from $36 on January 1st to an incredible $100 on March 22, in a rally that supposedly left investors “scratching their heads.”

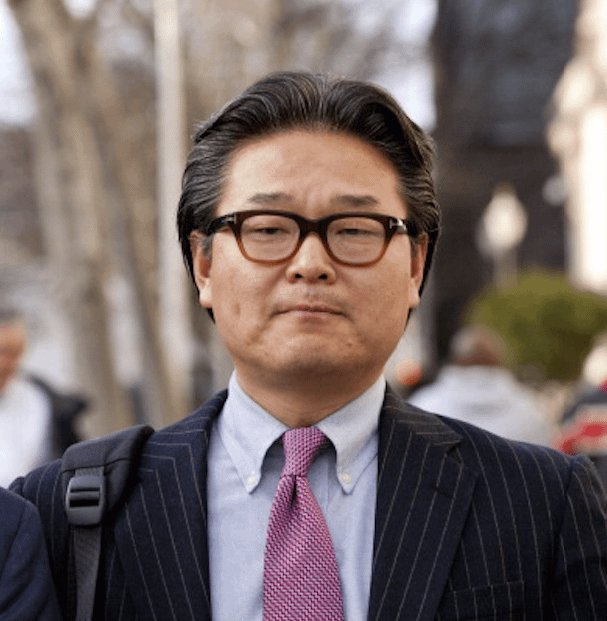

There was no million-member army of Redditors to focus on in these cases. The rallies of Viacom, Baidu, Discovery, GSX, Tencent Music Entertainment Group, Vipshop Holdings, Farfetch, and IQIYI Incorporated — all targets of institutional short sellers — were at the center of an elaborate, multi-billion-dollar short squeeze play by a single SEC-sanctioned Jesus freak of an investor: Sung Kook “Bill” Hwang, head of a fund called Archegos.

Once fined $60 million and banned by the S.E.C., Hwang as a character is a compelling fusion of religious weirdness and old-fashioned manipulation. He claims he invests “according to the word of God,” and he’s “not afraid of death or money,” allowing him to be “fearless” and “free” from concern about consequence. “The people on Wall Street wonder about the freedom I have, actually,” he said two years ago, ominously.

Despite throwing off a crazy vibe strong enough that the average person would cross the street to get away, he was able to borrow gargantuan sums — billions — from the world’s biggest banking institutions, using them to place a string of long bets that single-handedly sent the share prices of major companies skyrocketing.

Firms like Goldman, Sachs, Morgan Stanley, JP Morgan Chase, UBS, Japan’s Nomura, and Credit Suisse helped Hwang arrange his investments in the form of swaps. In return for collateral, banks would buy his targeted stock in four, five, six, even seven times the amount posted, then hold it on their own balance sheets. If the stock went up, the banks paid Hwang. If it went down, Hwang owed more.

The arrangement allowed Hwang to evade S.E.C. regulations requiring any investor who amasses more than 5% of any stock to issue a public filing as a beneficial owner. So enabled, Hwang quietly racked up more than 10% of the float of all his target companies, and as much as 30% interest in some of them, a setup that created massive systemic risk, but to the banks looked like an easy source of funding and management fees.

The current legend is that each of the banks thought they were the only ones doing the bad thing. Even the “smartest guys on the Street” at Goldman supposedly did not put two and two together, or wonder if Hwang was peddling the same trade to other shops. As a result, Hwang was allowed to keep bidding up and up until it all came crashing down in late March.

The end came after the CEO of Viacom, Bob Bakish — perhaps moved by a 73% jump in the firm’s share price — came to Goldman and Morgan Stanley on March 24th, asking to “discreetly” unload $3 billion in securities in an overnight sale. As one hedge fund analyst put it this week, this “might have been the what-the-fuck moment” for those two banks, who finally put two and two together.

Others scoff at the idea that firms like Goldman and Morgan Stanley didn’t see what was going on. “Even if they didn’t talk (and we know they do), they could all see the stock action as the prices ratcheted up over a relatively short period of time, and they could see each other’s increasing holdings albeit in the aggregate,” says Dennis Kelleher of Better Markets. “These guys are market makers, after all, and see the flow and have eyes and ears everywhere. Not credible.”

No matter how it happened, within a day after Bakish moved to sell those 20 million shares at $85 — the firm claimed, ludicrously in hindsight, that they were just raising money “for general corporate purposes, including investments in streaming” — the banks began demanding Hwang post more collateral. When he couldn’t meet his margin calls, the dealers one-by-one dumped his shares into the market, characteristically led by Goldman, which claimed to escape with “immaterial” losses thanks to its quick exit. “How are they always the only guys who don’t get carried out on a stretcher?” asks short-seller Marc Cohodes.

The Archegos story broke back on March 26th. Since then, Wall Street has been scrambling to contain both the financial and reputational damage. To date, the monetary hit to the banks alone is said to be $10 billion, but that number keeps rising, as Nomura and UBS only just this week disclosed a combined $3.7 billion in losses. Meanwhile, some analysts think the total loss in market value due just to this episode might ultimately be as big as $100 billion — one source thinks the number might be $200 billion.

Most of the straight-news coverage of Archegos has been of the “Who was that masked man?” variety, i.e. profiles of the terrible rogue trader who hit poor Wall Street like a weather event, a stroke of random luck. “He built a $10 billion empire. It fell apart in days,” was the New York Times offering, one of many stories to describe Archegos as a self-contained disaster.

The real issue isn’t Hwang but his banks. Just like 2008, some of the “tertiary” players rushed to give Hwang the extra “goodies” McDonald described, likely in the form of more leverage. The company destined to wear the historical dunce-cap this time a la Lehman looks like Credit Suisse, which has at least $5.5 billion in Hwang-related losses and has already fired investment bank chief Brian Chin and chief risk officer Lara Warner.

With firms like this in a race to shower even the most preposterous clients with unlimited funds, the grim reality of finance in the post-CARES Act era is that anyone with a tie and a business card can borrow enough to blow a $100 billion hole in the economy without being detected.

This raises the question: how many more Hwangs are out there? Not many people think he’s the only one.

“The system can’t take many more of these,” says McDonald.

“I think this guy [Hwang] is running the biggest Ponzi since Bernie Madoff, maybe bigger,” says Cohodes.

Like the failure of the two subprime-laden hedge funds that led to the collapse of Bear Stearns in 2008, Archegos exposed a rat’s nest of bad practices. Hwang was able to traipse through the system in part because Archegos is a “family office.” In theory, family offices provide a framework to manage money for individual wealthy families. In reality, it’s a loophole allowing mega-borrowers to be regulated less than the smallest retail consumers. As McDonald points out, if an ordinary person maxes out credit cards before a trip to Vegas, that person’s FICO score pings. Yet a tire-fire like Hwang buying swaps can make trades of a billion, even ten billion dollars without it registering anywhere.

This is the same problem we saw in 2008, when banks and hedge funds created mountains of theoretical risk (which became trillions in real losses) using derivative products like credit default swaps. Despite years of loud debates around the Dodd-Frank Act, the lack of even a basic tracking mechanism for such unexploded risk remains. “There are no leverage controls whatsoever. The only leverage control is market discipline,” sighs Marcus Stanley of Americans for Financial Reform.

Another common factor between 2008 and now is the hyper-availability of leverage, distributed on tap by Too Big To Fail Banks to all comers. Then the inappropriate borrower might have been an ordinary person buying too much house, or a company like AIG writing millions in synthetic mortgage insurance it never planned on honoring. This time it’s a known, SEC-sanctioned freak show taking out billion-dollar bank loans to bet on black at the roulette table. The issue isn’t that people like Hwang are out there, it’s that all of Hwang’s bankers went along with this game, hugely amplifying the irresponsible gambling.

“Hwang was basically using the balance sheets of Goldman and Morgan Stanley against the hedge funds,” says McDonald.

“Regulators have no chance,” says the hedge fund analyst. “Every time they tidy up one area, the rats just find a new hole to chew.”

The symbiotic relationship between banks that are overeager to lend and rapacious (or, in the case of Hwang, sociopathic) clients gambling with other people’s money is what blew up firms like Lehman. In order for those romances to happen, compliance officers can’t get in the way, and they don’t. The Hwang episode revealed that even in top-drawer firms, the dumbest people on the roster — usually, the salespeople on prime brokerage desks — have almost total autonomy.

Even Goldman placed Hwang on a “blacklist” as recently as 2018, yet suddenly reversed course and lent him enough money to make him the de facto owner of Viacom, suggesting that compliance even at the storied industry leader is a joke.

“A compliance dept at a big bank is nothing but a fig leaf,” says former Lehman lawyer and whistleblower Oliver Budde. “Things get flagged by line personnel, sure, but then they get overruled. If… internal rules are all being evaded, that does not matter if the boss says it is okay.”

With a few exceptions, financial professionals don’t mind being ripped as unethical. The dirty secret they do want covered up is that they’re not that smart. In the Covid-19 age especially, there’s a lot of subsidized mediocrity.

“All of these huge hedge funds have shitty performance, disguised by leverage,” says Cohodes. “If the markets go up 12% a year, you go up 5%, but you lever up seven times. Now it’s 35% and you’re getting three and thirty.” The top hedge funds charge 3% fees on assets under management and 30% of net gains.

That’s a great deal under any circumstances, but even better when 70-80% of your “performance” comes from being lent money by Goldman or Morgan Stanley or Credit Suisse, and even better still when you and your bank artificially drive up your gains together by pumping up the market. With limitless leverage, banks and hedge funds can in this way partner up to print themselves profits forever, until of course something goes wrong. With Archegos, something did go wrong — even on Wall Street, really dumb chasing really crazy eventually cracks up — but does anyone think there isn’t more?

Read the rest here…

Tyler Durden

Fri, 04/30/2021 – 17:00